--by Hannah Carney, History Resource Writer

As the History Resource Writer, I worked on this project with one central goal: to make the source sets more accessible to students. In order to help students build knowledge about historical events and people, we first needed to break down barriers, both intellectual and physical, to gaining that knowledge and understanding.

Source Selection

Fred Tangeman, Jenny Barr, Beth Hessel, Nancy Taylor, and other project leaders had already met with Abby Reisman, a professor of education at UPenn, whose research areas include how teachers teach history through the use of primary source research. I had studied with Abby in the Master of Science in Education program at UPenn, and when I came on to the project, Abby had already discussed with the BKBB leaders ways they could provide background information about the primary sources. The aim was to give students a better start at interpreting the sources’ content, tone, perspective, relevance, and reliability.

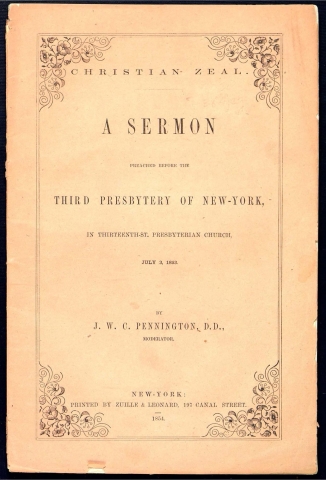

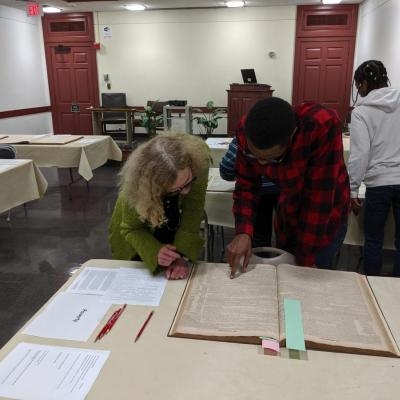

I began by reading through the source sets that Presbyterian Historical Society archivist Jenny Barr had already created and that had been used by Community College of Philadelphia students in previous visits to the PHS archives. To make these sets, Jenny had worked closely with CCP professors Joel Tannenbaum, Dave Prejsnar, and Anyabwile Aaron Love, and retired CCP professor Jackie Akins to find topics relevant to the course content each professor was teaching. Next, Jenny did the meticulous work of finding primary sources in the PHS archives that fit the topics and could also bring an interesting perspective to them. Sometimes--with advice from the professors--Jenny selected one or more secondary sources that complemented the primary sources and provided additional historical context and historiographical detail that the students would likely not have found on their own.

One of the most exciting things about the BKBB source sets is that a majority of them connect to African American History. The PHS archives are a wonderful resource for African American history, especially religious history, and these source sets showcase some incredible documents on topics that are especially relevant today. Given the demographics of the students visiting PHS for this project--about 72% are students of color at CCP--PHS staff and CCP professors made a conscious effort to provide multiple source sets focused on topics in African American history. As shown by the number of students who chose to write about these source sets--two- thirds or more of students across three classes--it seems evident that students gravitated towards those topics.

Helping Students Learn from Sources

Now my challenge was to remove barriers to students’ understanding of the primary and secondary sources in the BKBB source sets. One major barrier to understanding primary sources is the challenge of finding out who wrote the source, and when, and then interpreting the source based on those facts. As education professor Chauncey Monte-Sano found in her 2010 study of high school juniors at various levels of history writing ability, most of these students did not pay adequate attention to who wrote a source they were reading, or whether it was a primary or secondary source (Monte-Sano, 2010, p. 552). To try to remove or at least lower this barrier, I would be writing a source note for every primary and secondary source that shared relevant biographical information about the author and when the source was written.

Another barrier to understanding primary sources is that students may not know the historical context of a source itself, and how that source fits into the context in which it was written. As Reisman and psychology professor Sam Wineburg wrote, teachers can help improve their students’ understanding of historical context in primary sources by providing background knowledge, asking guiding questions, and explicitly modeling contextualized thinking (Reisman, Wineburg, 2008, p. 203). For the BKBB project, I provided background knowledge in the form of a short general historical overview at the beginning of each of the source sets, and gave students reading questions that helped to guide them through the sources to find the main idea and the most important details.

After carefully reading through the sources, I began writing the three elements of the teaching materials:

- General historical overview of the topic: including in some cases a description of how the sources in the set fit into a narrative about that topic.

- Source note: basic biographical information about the author of a source and when it was written; additionally, this could include details about the person’s identity that could shape their perspective on the subject.

- Reading questions: including both basic comprehension questions and others aimed at encouraging students to practice historical thinking.

To write those three elements, I found information in multiple sources. Occasionally the secondary sources that Jenny included in the set or listed as suggested reading provided the background information I needed to write the source notes. Most of the time I did additional research, starting always with the archive from which all these primary sources came: PHS. I started by searching the society’s website and online catalogs, especially for information about sources and authors that I knew were Presbyterian or had ties to the Presbyterian church, and then moved to the society’s Pearl digital archive if the former search didn’t reveal what I needed.

Next I searched Google Scholar to see if I could find academic articles with more information to add to my source notes and general historical overview of the topic. The Library of Congress and Encyclopedia Britannica were also helpful sources of specific and more general information, respectively. I also found that registering for a free account on JSTOR allowed me to access many scholarly articles that provided the details I needed for the source notes and historical overview. At no point in my research was it necessary to pay for a source of information. This is particularly important for archivists, teachers, and professors to understand, since research costs could be a barrier to creating these important learning supports for students.

For some sources, I felt that additional historical context was needed in the source note, to explain something that was particularly complex about the time period. This was the case for the Eric Ledell Smith secondary source, for which I provided extra background on the largest political parties of the time since they were so different than the parties we know today (Whigs and Democrats, rather than Democrats and Republicans). The more complex the issue at the heart of the source, the more likely I was to provide more information to support students’ understanding of the source.

For the reading questions, I wrote a combination of comprehension-type questions to guide a student through the source, and questions to encourage more complex historical thinking. For both types of questions, I usually included page numbers as checkpoints to help walk students through the source step-by-step. Comprehension questions always included some version of “who wrote the source and when?” to encourage students to look back at the source note, the citation, or the title page of the source itself. Professor of Education Christine Baron notes how difficult it is to teach students the skill of contextualization, and quotes Reisman in saying that a majority of students ignore citation information when they start reading a source (Barron, 2016, pp. 516, 527). My hope was that the source note itself, and then a reading question directing students to the source note, would help students do a better job of “sourcing”--determining who wrote the source, what their perspective was, and when it was written.

For historical thinking questions, I encouraged students to corroborate what they had read in another source, or to contextualize the source--to show how it fits into the historical context in which it was written. For example, in the Philadelphia Bible Riots of 1844 source set, one source, an essay by Walter Colton, was written in response to another source in the set, an essay by Bishop Kenrick. One of the reading questions for the Colton essay asked the reader to compare what Colton was writing to what Kenrick had written in his essay, therefore encouraging the reader to corroborate what she had read in the two sources.

Improved Student Understanding of Sources and Historical Contexts

I was gratified to hear from professors that the students seemed to have a better understanding of the sources when they had access to the background information, source notes, and reading questions, as compared to students who only had the sources. In one particular case, before the learning supports were written, four out of six students writing about the Temperance Movement misinterpreted a source and thought it was an anti-temperance document. The next semester, when different students taking the same class had access to the learning supports, all of the students who cited that source interpreted it correctly, understanding that it was a pro-temperance advertisement.

I hope that archivists, teachers, professors, and other educators will feel encouraged not only to use the background information, source notes, and reading questions that we created for this project, but will also feel empowered to create their own learning supports for any primary or secondary sources that could enrich the topic they are teaching. These supports go a long way towards breaking down barriers to student understanding, and they can be written using research tools that anyone can access.

Works cited:

Baron, Christine (2016), “Using Embedded Visual Coding to Support Contextualization of Historical Texts.” American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 53, (No. 3), pp. 516-540.

Monte-Sano, Chauncey (2010). “Disciplinary Literacy in History: An Exploration of the Historical Nature of Adolescents’ Writing.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences, Vol. 19 (No. 4), pp. 539-568.

Reisman, A, Wineburg, S. (2008). “Teaching the Skill of Contextualizing in History.” The Social Studies, pp. 202-207.