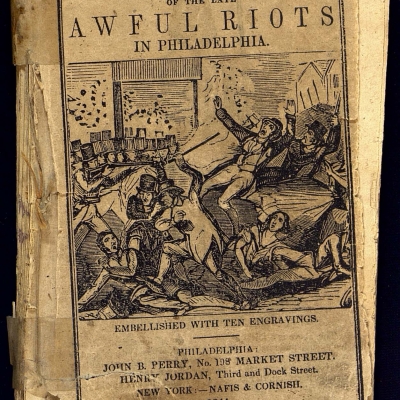

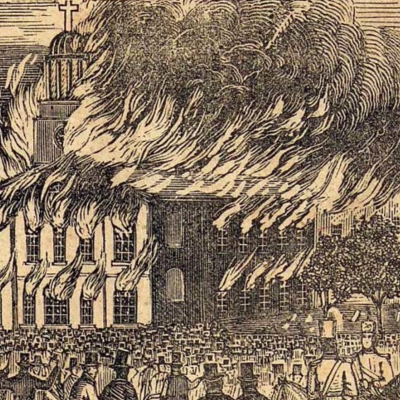

The Philadelphia Bible Riots took place in the spring of 1844, in the largely Irish immigrant neighborhood of Kensington. On May 6th, 1844, members of the Native American Party, an anti-Irish, white Protestant political group, gathered directly across from the main Irish market in the neighborhood to hold a rally upholding the use of the Protestant Bible in Philadelphia public schools. A previous meeting three days before had been interrupted by local Irish people who disagreed with the speakers. This time, rain pushed the Native American Party rally inside the Nanny Goat Market, and nativists and Irish people started to fight in the crowd. The violence soon escalated with shots fired, and then grew into a massively destructive riot, with Irish people shooting out of buildings and from behind fences, and then as many as 3,000 nativists roaming the streets, setting fire to buildings, and over a period of three days, burning two major Catholic churches and multiple buildings. At least 20 people died, thousands were displaced (mostly Irish), and a low estimate of the property loss was $250,000, or about $6.8 million in today’s money.

The primary cause of the Philadelphia Bible Riots was a disagreement between Catholics and Protestants over how religion should be presented in public schools. Long before stricter separation of church and state regulations moved religion out of the American public school classroom, the questions surrounding what Bible to use, what hymns to sing, and what prayers to lead were serious. In the case discussed here, Philadelphia Catholics objected to their children being taught from the main Protestant version of the Bible, the King James version. They also balked at having Protestant prayers and hymns taught in school, and rejected anti-Catholic books and materials that were often used in schools. The Catholic Bishop of Philadelphia, Francis Kenrick, wrote to the Board of Controllers of Public Schools in late 1842 to communicate these complaints, and the reaction from Protestants in the city (and outside of it) was swift and overwhelmingly negative.

As with many conflicts between groups, the discord between Catholics and Protestants also had significant ethnic, cultural, and political overtones. Protestants were largely of English and Scotch-Irish heritage, and had been in United States for more than a generation. Most of the Catholics in the United States were recently arrived immigrants from Ireland. Almost half of all immigrants to the United States in the 1840s were Irish Catholics, especially after the potato blight of 1845 made life in Ireland untenable for many people. By the 1840s, many U.S.-born Protestants felt threatened by the influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland, as well as Germany, and formed nativist political parties such as the Native American Party that aimed to protect the rights of “Native Americans.” Nativists set themselves above the Irish by lambasting their religion, their supposed excessive drinking, and their alleged laziness and stupidity, while promoting Protestantism, temperance, and the Protestant work ethic.