“…And repent: i.e. Candidly confess, and sincerely lament your Coldness and Negligence in Time past, and resolve in the Strength of God to do better in Time to come, in Pursuance of which, strive to keep yourselves in the Love of God, strive to keep alive in your Souls the sacred Fire of divine Grace, that ye may not be dead while ye live, but live in Love, live to God, and feel you live!”

-Gilbert Tennent, 1760

The Great Awakening was a tremendous religious revival that began in England and Scotland and spread to the British colonies in North America in the 1730s. George Whitefield (1714-1770), an Anglican minister from England, arrived in 1739 and began a widely publicized and wildly popular tour of the colonies. Whitefield was a highly charismatic evangelical preacher who asked that his congregants look within themselves for the “indwelling of Christ” to know if they were true Christians and thus saved from hell.

Whitefield and other revivalist ministers of the First Great Awakening described hell in terrible detail and emphasized how sinful most people were. They also criticized other ministers for focusing too much on rational, intellectual faith and good works, rather than an emotional, passionate, deeply felt experience of faith in God.

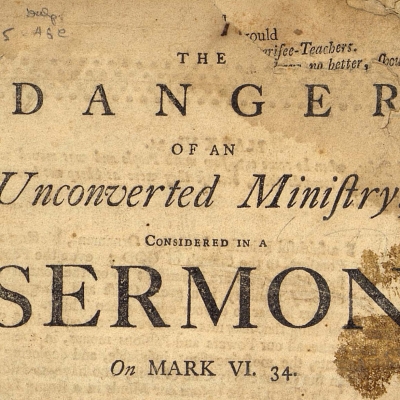

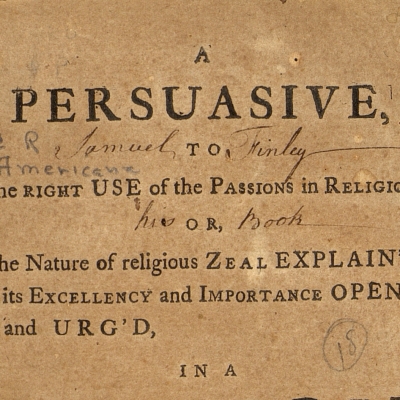

Presbyterian minister Gilbert Tennent (1703-1764), like Whitefield, had his own intense conversion experience and as a young minister was a zealous proponent of revivalist religion. Tennent attacked the religious establishment for trying to limit the ordination of new clergy by requiring American-born ministers to attend the few colleges and seminaries in the colonies at that time. In a sermon from 1742, Tennent fiercely condemned his more conservative colleagues for frowning upon itinerant preaching—a mainstay of revivalism—and for not adequately impressing their congregations with the horrors of hell. Tennant and other revivalist preachers helped bring about a schism in the Presbyterian church between Old Side, traditional ministers and New Side, revivalist evangelical ministers. After the 1741 split, the two sides reconciled in 1758.

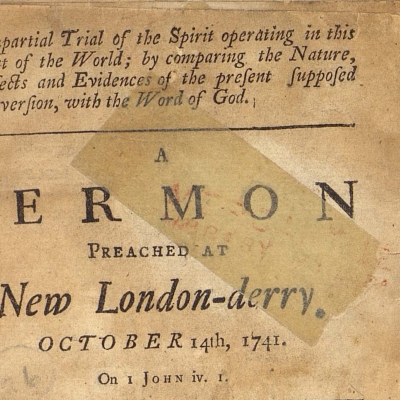

Offering a strong rebuttal to revivalists like Tennent, Irish minister John Caldwell painted revivalists as overly dramatic and out of control. Caldwell claimed that there was no way to verify that a person’s conversion experience was authentic, and that asking for proof often invited a defensive attack from the converted person. Just as the revivalists defended their concept of Christian faith, Caldwell held that the more traditional, rational expressions of faith were correct and acceptable to God.