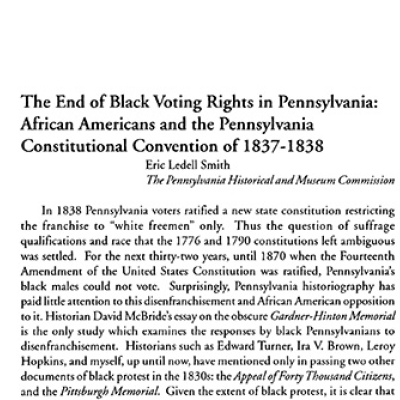

Attempts to gain voting rights for African Americans began long before the Civil War and the passage of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution in 1870. Free black people were able to vote in a few northern states including Pennsylvania until 1838, and some exercised that right, though they were often met with hostility at the polls.

The Pennsylvania Constitution of 1790, like the US Constitution it was modeled on, left the voting rights clause vague and allowed for differing interpretations of who had the right to vote. Some free African Americans and white supporters believed that “every freeman” in the state constitution included free black men, and a small though unknown number of black men did vote in some Pennsylvania elections between 1790 and 1837. Still, in practice, the vast majority of free black men in Pennsylvania were forced by intimidation and threats of violence to stay away from the polls.

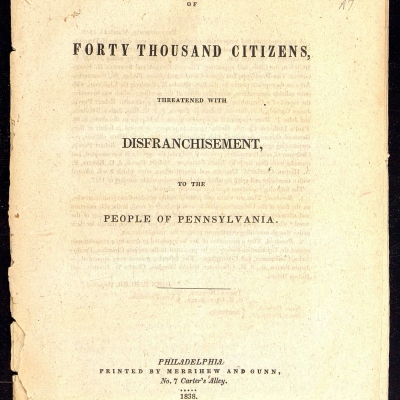

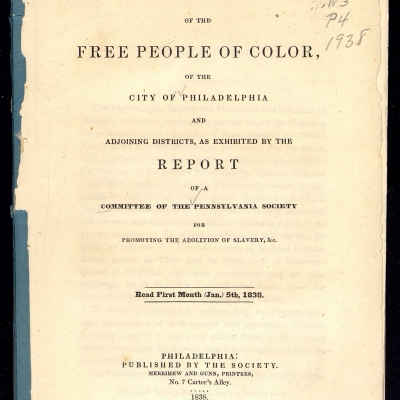

In late 1837 and early 1838, when Pennsylvania statesmen were gathered for the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention, state Democrats lobbied hard for an amendment to the constitution that would ban black men from voting in state elections. Free African American men, especially James Forten Sr., James Forten Jr., and Robert Purvis in Philadelphia, and John Vashon and John Peck in Pittsburgh, fought to retain the right to vote that, at least in theory, existed in the Pennsylvania Constitution. These men wrote and supported the Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens and the Pittsburgh Memorial, respectively, to defend the right of free black people to vote based on their US citizenship, the taxes they paid, and the principles of freedom and equality enshrined in the US Constitution.

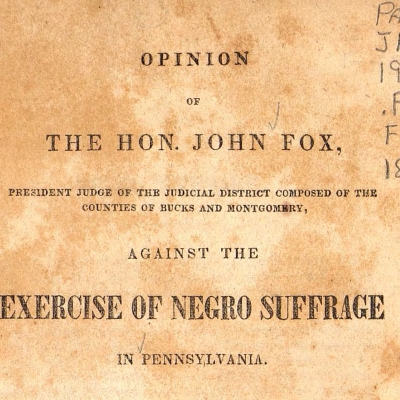

The delegates at the convention in the end voted to add the amendment denying black suffrage, and it was narrowly approved by a popular vote soon after. The 1837-1838 Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention confirmed the dominance of white supremacy in the state of Pennsylvania and in effect stalled the cause of black suffrage for 32 years.