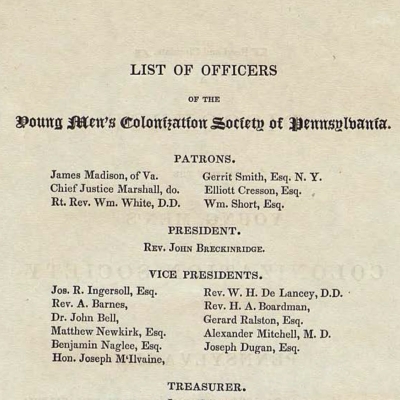

The Colonization Movement was an effort to bring free African Americans from the United States to Africa. Though the idea of colonization dates back to the 18th century, it took off in the 19th century with the founding of the American Colonization Society (ACS) in 1816. The main founder of the ACS was Presbyterian minister Robert Finley, and other early members included Kentucky statesman and slaveholder Henry Clay, Francis Scott Key (composer of the “Star Spangled Banner”) and George Washington’s nephew Bushrod Washington.

Members of the ACS had divergent views on why they supported colonization: some had a real interest in helping free African Americans escape the prejudice and violence they faced in the United States. Others, including Finley, thought African Americans would never be able to integrate into normal life in the United States because of their inherent inferiority and therefore should be separated from white Americans. He also hoped that expatriating African Americans to Africa would eventually end the institution of slavery. Still other pro-slavery supporters of colonization wanted to move free African Americans to Africa because they were seen as a threat to the institution of slavery.

The great majority of the ACS’s members were white, though some African Americans supported colonization. Colonization supporter Paul Cuffe, of mixed African and Indian ancestry, wanted free blacks to build new communities of dignity and independence in Africa, the homeland of his forebears.

Still, many African Americans opposed colonization as a thinly veiled attempt to rid the United States of its free African American citizens and allow the institution of slavery to continue unquestioned. Opponents of colonization such as Frederick Douglass wanted to focus on making the lives of free African Americans better in the United States, and to help enslaved African Americans by fighting for abolition. Free black Philadelphians such as James Forten, Absalom Jones, and Robert Purvis were vocally opposed to colonization, along with Pittsburgh black leaders such as John Peck and John Vashon.

Both white and black abolitionists, many of whom supported the immediate abolition of slavery in this country, tended to oppose the Colonization Movement. By the 1830s, this opposition was strong, with resolutions by the 1837 Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women and other abolition groups stating their opposition to the ACS.

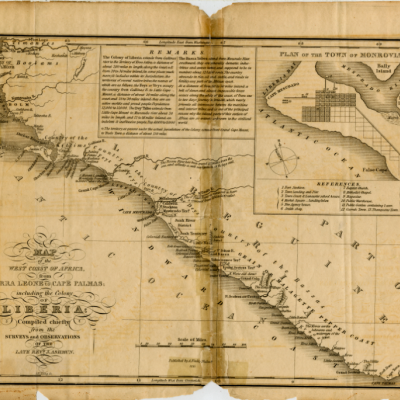

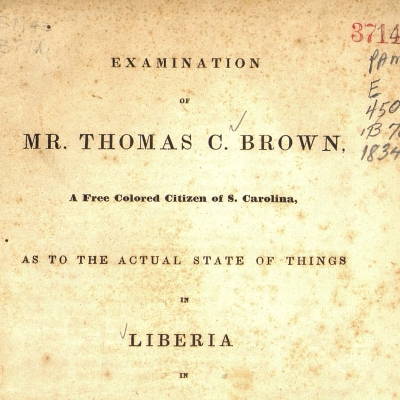

The ACS did acquire land in West Africa, much of what is now the country of Liberia, and sent as many as 10,000 freed black slaves and free African Americans to the colony between 1821 and 1867.