At the time of the Revolutionary War, American slavery had been in place for almost 160 years and was a major source of labor in the 13 colonies. Just as this system of human trafficking and forced labor became more entrenched in the southern colonies, and with many of the founding fathers both owning slaves and supporting the institution, anti-slavery sentiment also began to grow and spread. Especially as white colonists rallied around the cause of freedom from British rule and equality for all men, the hypocrisy of the slave labor system became more apparent for many people.

Additionally, well known Africans and African Americans such as the poet Phyllis Wheatley, the writer and naturalist Benjamin Banneker, and the former enslaved explorer and writer Olaudah Equiano provided proof of Africans’ intelligence and potential in terms that European Americans could understand and appreciate.

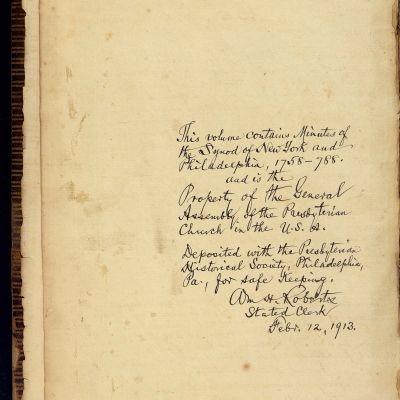

Though Quakers had expressed anti-slavery views as early as 1688, organized opposition to the institution took much longer to develop. The main ruling body of the Presbyterian Church in America drew national and international attention in 1787 when it recommended that members of the church “do everything in their power…to promote the abolition of Slavery, and the instruction of Negroes whether bond or free.” Though definitive in its stance on slavery, the church stopped short of censuring or expelling slaveholding Presbyterians, and qualified their stance on slavery with the warning that enslaved people would not be ready for immediate emancipation. In this way the Presbyterian Church helped set a precedent that would be used for the next 70 years or so: taking a moral stance against slavery with no serious action to dismantle the institution.

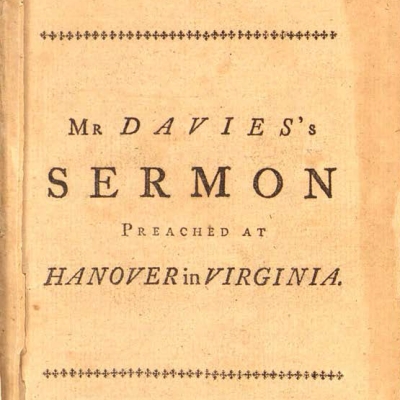

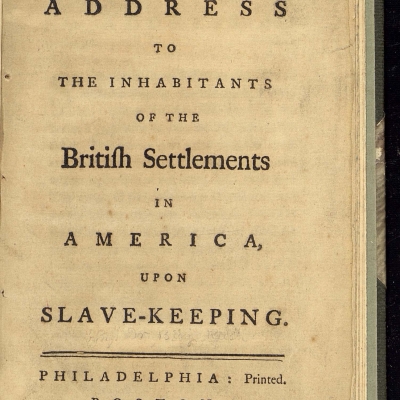

Samuel Davies (1723-1761) and Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) each wrote eloquently during the revolutionary era about the evils of slavery, though both men at some time in their lives owned slaves and benefitted from the American slave labor system. Davies focused on the spiritual equality of enslaved people (all humans have souls) and the responsibility of masters to educate and bring slaves into the Christian faith, while Rush nearly 20 years later promoted full abolition and outlined the steps to get there.

William Harrison Taylor, who currently teaches history at Alabama State University, writes about the Presbyterian Church’s 1787 decision to promote abolition. Adding to previous scholarship on this subject, Taylor argues that it was not just racism, but also church precedent in dealing with conflict, that made the Presbyterian Church promote abolition while refusing to condemn slaveholders directly or work towards immediate emancipation.