The Presbyterian Church in the United States, like the country, itself, was divided over the issue of slavery. Well known Presbyterian ministers such as Charles Finney, John Rankin, and Albert Barnes publicly opposed slavery and advocated for abolition, while other ministers and church leaders such as Henry Van Dyke, Benjamin Morgan Palmer and James Henley Thornwell defended slavery, claiming the institution was sanctioned by their faith and by God.

Most white American Presbyterians were of Scotch-Irish heritage, settling in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains and throughout the mid-Atlantic region. Of these early American Presbyterians, many lived among slaveholders and likewise, owned, traded, or were overseers of enslaved African Americans. Opposition to slavery, however, was not uncommon among Presbyterians. As early as 1787, the Presbyterian Synod of New York and Philadelphia declared its support for abolition, and in 1818, the General Assembly of the church condemned slavery as going against moral correctness and the laws of God.

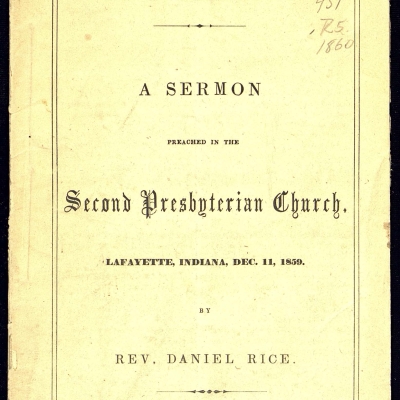

Although the schism of 1837 that divided the Presbyterian Church into the Old School and New School principally came about due to doctrinal differences and conflicts over religious revivalism, the issue of slavery also played a role. Old School Presbyterian, Henry Van Dyke of Brooklyn, (author of Document 2 in this set) was not only sympathetic to slaveholders, but was staunchly anti-abolition, claiming that abolitionists were divisive and unchristian in their methods. On the other hand, renowned revivalist Presbyterian, Charles Finney, and other New School Presbyterians such as Albert Barnes and Lyman Beecher (the father of Uncle Tom’s Cabin author, Harriet Beecher Stowe) were adamantly opposed to slavery and supported the cause of abolitionism. African American Presbyterian ministers such as Henry Highland Garnet, James W.C. Pennington, and Theodore Wright all spoke to their congregations about the evils of slavery and the need to reach out and help their enslaved brethren.

After the start of the Civil War, the Presbyterian Church would split again, this time, between the North and the South. But as of 1860, Presbyterian attitudes toward slavery did not divide neatly along the Mason-Dixon Line. The Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 had all increased tension between pro-slavery Americans and abolitionists. Also, radical abolitionist John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859 seized the attention of the nation and foreshadowed the bloody civil war that would begin less than two years later. As with many other Protestant denominations in the United States, the Presbyterian Church did not have a unified perspective on the issue of slavery, and individual ministers and parishioners grappled with the issue in their own ways.