As Union armies marched through the south during the Civil War, thousands of enslaved people left the plantations and farms of their owners and sought protection from and jobs with Union forces. General Benjamin F. Butler in Virginia was the first to designate these people as “contraband of war” because they were formerly Confederate property and they had been used in the fight against the Union. They could, therefore, be seized by Union forces, thus becoming Union property; they were not officially emancipated.

But these people, seizing the opportunity to escape the oppression of chattel slavery, helped to shape the way that emancipation unfolded gradually throughout the course of the war. As Eric Foner describes in his 1990 book A Short History of Reconstruction, a first step toward emancipation was the article of war enacted by Congress in March 1862 that barred Union armies from returning escaped slaves to their former owners. Next, Washington, D.C. slaves were set free, and soon after that, enslaved people living in the territory occupied by the Union were freed, as well as those who were able to escape to Union-occupied territories. Finally, the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 freed some, but not all enslaved people—those living in the border states were excluded.

The 180,000 African Americans who served in the Union army were crucial to the emancipation process. Most of these soldiers had escaped from their masters and sought jobs in the army to support the Union and to help bring about emancipation. Military service launched many political careers among newly freed African American men, as Foner points out, including four United States Congressmen.

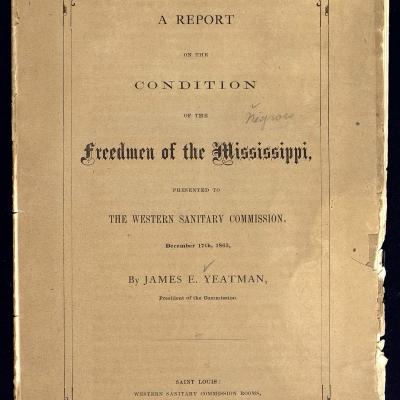

Military-aged black men were not the only people escaping from slavery during the Civil War. Women, children, and older men also fled, and the U.S. government and private agencies provided basic accommodation in camps throughout the south. Schools were set up in some of the camps, and many residents and leaders of these settlements advocated for self-governance and independence for the newly free African American communities. Conditions varied widely between camps, however, and disease spread quickly due to overcrowding, lack of proper sanitation, and other forms of government negligence. Additionally, the U.S. government paid well below market wage to African Americans doing government work, as observers such as James Yeatman pointed out.

Freedmen and women faced serious challenges after escaping from slavery during the Civil War, not the least of which were the racism and hostility of their “reluctant liberators,” as historian Vincent Harding called the Union army. Still, they were able to help shape what emancipation would look like for all African Americans at the end of the Civil War.