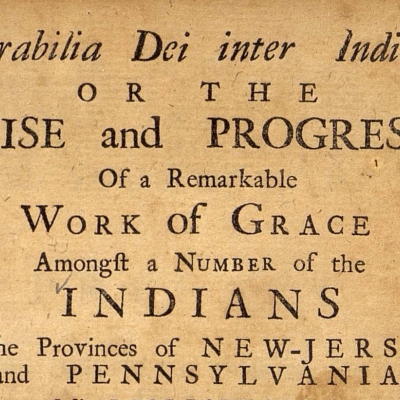

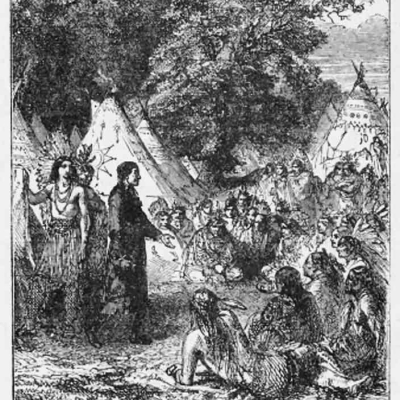

Protestant missions to the North American Indians began in the early 1600s in the Virginia colony and in New England. In the latter, Puritans had come to settle on land either bought and stolen from Native Americans in order to build religious communities and practice their faith without the government and societal persecution they had faced in Europe. In addition to seeking converts to Christianity, New England Puritan missionaries attempted to assimilate Indians to English customs and train them to become yeoman farmers. Presbyterian missionary David Brainerd (1718-1747) came out of the Puritan missionary tradition in Connecticut, but was also strongly influenced by the First Great Awakening that brought religious fervor and a wave of evangelism across the British colonies in the 1730s and 1740s.

The underlying assumption among early colonial Protestant missionaries was that Native American culture, language, and religion were inherently inferior to those of the English, and that the Indians should not only convert to Christianity but also give up their traditional ways in order to embrace the English way of life. Not surprisingly, many Native Americans resisted conversion to Christianity by missionaries that they viewed as part of the exploitative English colonial system. David Brainerd wrote about his interactions with Indians who declined to convert to Christianity for those and other reasons, such as their objection to white settlers’ drunkenness, violence, and distribution of alcohol to the Indians. Many Indians did decide to convert to Christianity, however. For those who became Christians, conversion and the adoption of at least some English customs allowed for greater political and social autonomy and, in some cases, the retention of their land.

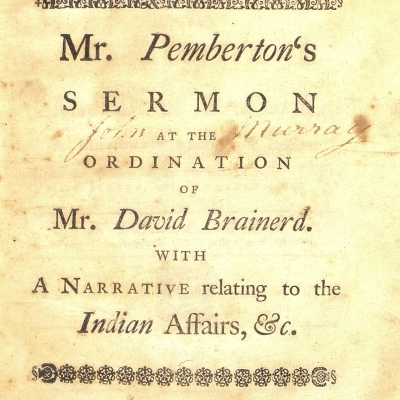

David Brainerd became famous after his death largely due to the work of his friend and supporter Jonathan Edwards, the renowned theologian and a central figure in the First Great Awakening. Brainerd has since become a figurehead for multiple groups and causes, especially evangelical Protestants and missionaries, who have lionized him for what they see as his self-sacrificing, devout, divinely inspired work among the Indians. More recently, historians have critiqued Brainerd’s apparent lack of respect for and real interest in the Indians he worked to convert in his missionary years. These historians have also demonstrated his ineffectiveness, both as a missionary and as an advocate for Native Americans. In his complexity, and especially in the ways that he both followed and deviated from typical colonial missionary work, Brainerd is a helpful figure to examine in order to better understand early Protestant missions to the Native Americans.